Developed as a project of the California State University system, UDL-Universe (UDL-U) supports postsecondary faculty and staff by providing resources and examples to improve postsecondary education for all students, including those with disabilities. UDL-U is designed to be useful for individual inquiries related to small UDL topics, issues, or problems, as well as scalable to larger faculty development efforts (e.g., Faculty Learning Communities). UDL-U frames course redesign as a three-tier professional development process:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License.

The following guides support various levels of UDL professional development and course redesign. Each guide offers numerous resources including: campus promotional materials, UDL session planners, UDL curricula, UDL course implementation exemplars, and evaluation instruments. These resources have been successfully utilized by numerous postsecondary institutions in support of enhanced teaching and learning, for all students.

Throughout UDL-U, you will find content boxes that will provide faculty developers with additional strategies and resources for leading the implementation of UDL at your institution. These boxes are identified by an orange colored header, as well as the title "Faculty Developer Tips."

This site and contents of this site were originally developed through the Ensuring Access through Collaboration and Technology (about EnACT) project, funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education (P333A-080027). Additional funding has been provided through California State University, Academic Technology Services.

UDL has its roots in Universal Design, a term coined by Ronald L. Mace (North Carolina State University) in 1972, as a way to describe the concept of designing all products and the built environment to be aesthetic and usable to the greatest extent possible by everyone, regardless of their age, ability, or status in life.

The Disability Act 2005 defines Universal Design as:

When designing the physical environment, one must consider a wide range of populations and conditions. The example below allows for many options from unassisted stairs, stairs with handrail, or built-in ramp option for those with strollers, carts, or wheelchair.

The following seven principles were developed in relation to environments, products, and communications. Much of the principles and guidelines can be applied to the teaching and learning processes. The following was developed by the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University.

PRINCIPLE ONE: Equitable

Use

The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

Guidelines:

1a. Provide the same means

of use for all users: identical whenever possible; equivalent when not.

1b. Avoid segregating or stigmatizing any users.

1c. Provisions for privacy, security, and safety should be equally

available to all users.

1d. Make the design appealing to all users.

PRINCIPLE TWO: Flexibility in

Use

The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

Guidelines:

2a. Provide choice in

methods of use.

2b. Accommodate right- or left-handed access and use.

2c. Facilitate the user’s accuracy and precision.

2d. Provide adaptability to the user’s pace.

PRINCIPLE THREE: Simple and

Intuitive Use

Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge,

language skills, or current concentration level.

Guidelines:

3a. Eliminate unnecessary

complexity.

3b. Be consistent with user expectations and intuition.

3c. Accommodate a wide range of literacy and language skills.

3d. Arrange information consistent with its importance.

3e. Provide effective prompting and feedback during and after task

completion.

PRINCIPLE FOUR: Perceptible

Information

The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient

conditions or the user’s sensory abilities.

Guidelines:

4a. Use different modes

(pictorial, verbal, tactile) for redundant presentation of essential information.

4b. Provide adequate contrast between essential information and its

surroundings.

4c. Maximize “legibility” of essential information.

4d. Differentiate elements in ways that can be described (i.e., make it

easy to give instructions or directions).

4e. Provide compatibility with a variety of techniques or devices used by

people with sensory limitations.

PRINCIPLE FIVE: Tolerance for

Error

The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended

actions.

Guidelines:

5a. Arrange elements to

minimize hazards and errors: most used elements, most accessible; hazardous elements

eliminated, isolated, or shielded.

5b. Provide warnings of hazards and errors.

5c. Provide fail safe features.

5d. Discourage unconscious action in tasks that require

vigilance.

PRINCIPLE SIX: Low Physical

Effort

The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of

fatigue.

Guidelines:

6a. Allow user to maintain

a neutral body position.

6b. Use reasonable operating forces.

6c. Minimize repetitive actions.

6d. Minimize sustained physical effort.

PRINCIPLE SEVEN: Size and Space for

Approach and Use

Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless

of user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

Guidelines:

7a. Provide a clear line of

sight to important elements for any seated or standing user.

7b. Make reach to all components comfortable for any seated or standing

user.

7c. Accommodate variations in hand and grip size.

7d. Provide adequate space for the use of assistive devices or personal

assistance.

The term UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR LEARNING means a scientifically valid framework for guiding educational practice that:

Provided by the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 (HEOA).

In the early 1990's, we (CAST) shifted our approach to address the disabilities of schools rather than students. We later coined a name for this new approach: universal design for learning (UDL). UDL drew upon neuroscience and education research, and leveraged the flexibility of digital technology to design learning environments that from the outset offered options for diverse learner needs. This approach caught on as others also recognized the need to make education more responsive to learner differences, and wanted to ensure that the benefits of education were more equitably and effectively distributed. (p.3)

The term UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR LEARNING means a scientifically valid framework for guiding educational practice that:

Provided by the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 (HEOA).

In the early 1990's, we (CAST) shifted our approach to address the disabilities of schools rather than students. We later coined a name for this new approach: universal design for learning (UDL). UDL drew upon neuroscience and education research, and leveraged the flexibility of digital technology to design learning environments that from the outset offered options for diverse learner needs. This approach caught on as others also recognized the need to make education more responsive to learner differences, and wanted to ensure that the benefits of education were more equitably and effectively distributed. (p.3)

Learners differ in the ways that they perceive and comprehend information that is presented to them. For example, those with sensory disabilities (e.g., blindness or deafness); learning disabilities (e.g., dyslexia); language or cultural differences, and so forth may all require different ways of approaching content. Others may simply grasp information quicker or more efficiently through visual or auditory means rather than printed text.

What: Graphic Organizers are visual representations of knowledge, concepts, thoughts, or ideas. In addition, GOs have been known to help, relieve learner boredom, enhance recall, provide motivation, create interest, clarify information, assist in organizing thoughts, and promote understanding of content

How: Examples include:

Ways:

Professors and instructors can provide completed them to students (learn by viewing), have students construct their own (learn by doing), or have students finalize partially completed Graphic Organizers (scaffolding)

Graphic Organizers entered the realm of education in the late twentieth century as ways of helping students to organize their thoughts (as a sort of pre-writing exercise). For example, a student is asked, "What were the causes of the French Revolution?" The student places the question in the middle of a sheet of paper. Branching off of this, the student jots down her ideas, such as "poor harvests," "unfairness of the Old Regime," etc. Branching off of these are more of the student's thoughts, such as "the nobles paid no taxes" branching from "unfairness of the Old Regime."

Why: Positive effects on higher order knowledge but not on facts (Robinson & Kiewra, 1995); Quiz scores higher using partially complete GO (Robinson et al., 2006).

Learners differ markedly in the ways in which they can be engaged or motivated to learn. There are a variety of sources that can influence individual variation in affect including neurology, culture, personal relevance, subjectivity, and background knowledge, along with a variety of other factors presented in these guidelines.

How do I involve students in the learning process?

Knowing that active participation is key to learning, consider adopting various ways that students can actively participate in class. Active participation strengthens learning and, ultimately, the effectiveness of your instruction.

Take-Away Engagement Strategy: The Pause Procedure

What: Short (4-minute) periodic breaks to review notes and or discuss course content.

Why: Increases accuracy of notes (Ruhl & Suritsky, 1995); higher exam scores and less need for sustained attention (Braun & Simpson, 2004).

How: Pause at natural breaks (15 minutes). Provide clear instructions, signal beginning and end of Pause Procedure, and include time for unresolved questions.

Examples:

Learners differ in the ways that they can navigate a learning environment and express what they know. Some may be able to express themselves well in written text but not speech, and vice versa. It should also be recognized that action and expression require a great deal of strategy, practice, and organization; this is another area in which learners can differ.

How do I ask my students to show what they know?

Fundamentals in Practice: Knowing that students have preferences for how they express themselves, (orally, written, and visually), consider providing multiple ways for students to demonstrate their competency. This increases the likelihood of their success and ultimately, the effectiveness of how you measure their learning.

Take-Away UDL Strategy: UDL Course Rubrics

What: Scoring tool that explicitly represents the performance expectations for an assignment. Divides the assignment into component parts and provides clear descriptions of each component, at varying levels of mastery.

Why: Enhanced achievement and student satisfaction (Robyler & Wiencke, 2003); Reliable formative and summative assessment tool (Montgomery, 2002).

How: Consider major elements embedded in any given assignment. Define components and evaluation parameters.

Ways:

Universal Design for Learning in

Higher Education: From Principles to Practice by

Universal Design for Learning in

Higher Education: From Principles to Practice by

Teaching Every Student in the

Digital Age by

Teaching Every Student in the

Digital Age by

Universal Design for

Learning by

Universal Design for

Learning by

Teaching in Today's Inclusive

Classrooms: A Universal Design for Learning Approach by

Teaching in Today's Inclusive

Classrooms: A Universal Design for Learning Approach by

A Practical Reader in Universal

Design for Learning by

A Practical Reader in Universal

Design for Learning by

The Universally Designed Classroom: Accessible Curriculum And

Digital Technologies by

The Universally Designed Classroom: Accessible Curriculum And

Digital Technologies by

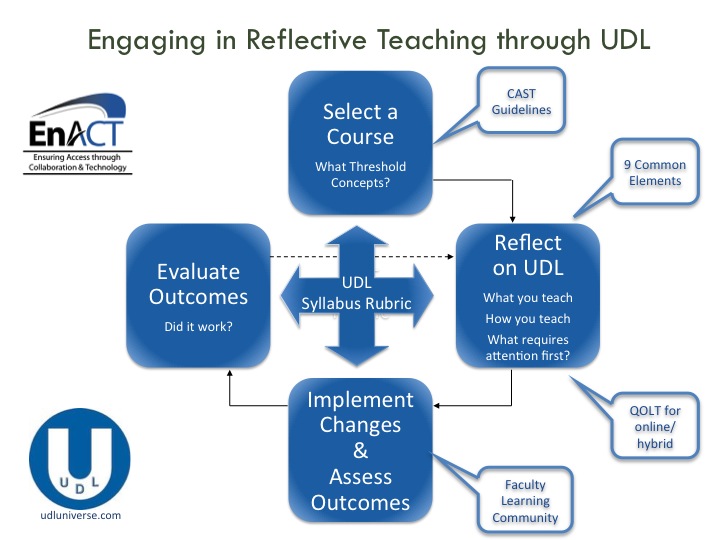

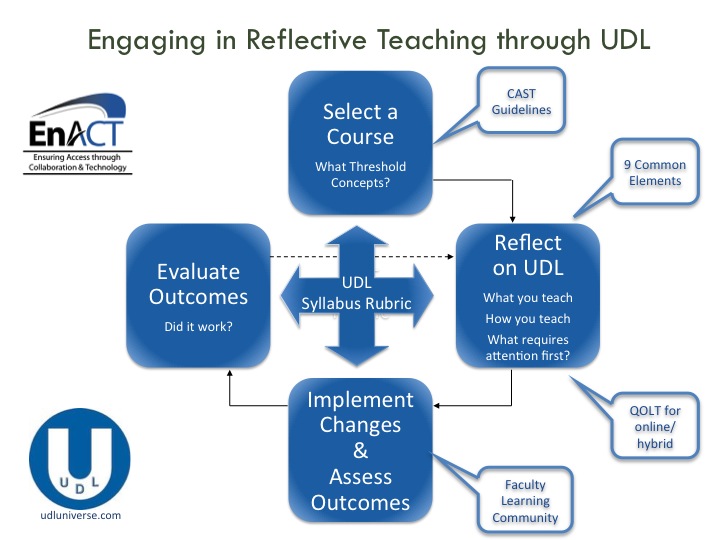

So how does one begin the course redesign or development process?

As noted in the graphic, the UDL Syllabus Rubric is a central element throughout this iterative process and is explained in greater depth in the next UDL Course Changes section.

The following Course Redesign Process graphic represents the steps

and primary resources to be used when working with faculty to make UDL course

changes.

So how does one begin the course redesign or development process?

As noted in the graphic, the UDL Syllabus Rubric is a central element throughout this iterative process and is explained in greater depth in the next UDL Course Changes section.

The following Course Redesign Process graphic represents the steps

and primary resources to be used when working with faculty to make UDL course

changes.

A well-designed syllabus establishes clear communication between instructor and students and provides the necessary information and resources to promote active, purposeful, and effective learning. Thus, syllabi serve as road maps that define the content and context of learning in our classrooms. While Universal Design for Learning often focuses on in-process course delivery, assignments, and assessments, it is important to recognize that syllabi can provide a larger content for how and where UDL can strengthen our teaching effectiveness.

Self-discovery related to course design and effectiveness.

Group Implementation:

The preferred method for using the UDL Syllabus Rubric is via in-depth, Faculty Learning Community process. This allows for simultaneous

self-reflection and peer-input. In addition, the FLC process is often interdisciplinary,

which helps reconsider from a different lens how to represent course material, engage students,

or assess their expression of learning.

Individual Implementation:

One can simply select a course syllabus and analyze it according to the rubric elements and

respective rating categories. For each element, there is also a Notes field that serves as

a place to record why a particular rating was given on a UDL syllabus element. By doing

so, the in-the-moment information is documented. In addition to better retaining the

information, prompts can be embedded, which serve as low-stakes self-contracts or reference

points for future areas of syllabus refinement.

The UDL Syllabus Rubric is often used by one faculty member to evaluate and give input to another. However, it is important to first establish an atmosphere of mutual respect and trust. Once this is done, faculty members are often more open to input by their peers. Once a faculty member receives input via peer-dialog and rubric documentation, that faculty member explores which changes are reasonable and what steps it may take. Often, the changes might be adding additional syllabus information to a specific section or simply reformatting a particular element. Importantly, FLC dialog often leads to further UDL-based course changes and reflections that benefit all participants.

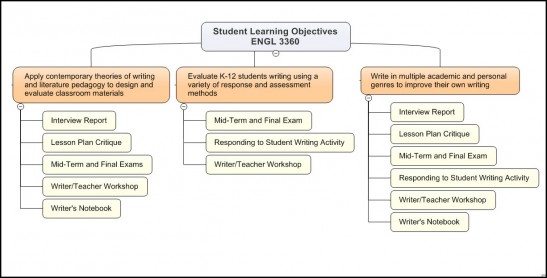

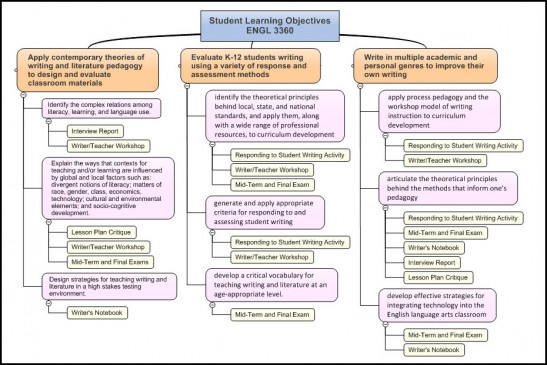

Articulating student learning outcomes (SLO) is a standard course and syllabus development process. SLO serve as checks for our course development, as we examine the end result of the course, how it contributes to student learning and development, and how the course contributes to the overall program (e.g., major, GE). Typical fashion is to list the SLO, sometimes called Course Objectives, in verti-linear bullet fashion. These are often glanced over and seldom revisited. In addition, there may be no representation as to how the SLO and student course experiences or requirements relate. Often, this leads to a disconnect, whether perceived or actual, between what the instructor expects and what students understand is expected.

However, a UDL Syllabus strategy for making SLO a more prominent focus, while adding to understanding of how the individual parts of a class constitute the whole (i.e,. the purpose), is to graphically represent them.

Below is an example for an Advanced Composition course. The three main objectives are represented in the orange boxes, while the modes for demonstrating competency in them fall below.

This next view goes beyond the broad objectives to discrete and measureable student learning outcomes, which are represented in the purple rectangles, followed by their respective modes of student expression.

One successful faculty development strategy is the utilization of the UDL Syllabus Rubric as a pre-post measure of faculty course change. When introducing UDL course changes, consider having faculty individually rate themselves on the UDL Syllabus Rubric. In addition to serving as an active engagement strategy during your workshop, this also provides an opportunity for faculty to begin connecting UDL strategies to their individual courses. As a culminating assessment activity, have faculty reassess themselves using the UDL Syllabus Rubric. This not only provides a measure of individual faculty growth, but is also a way to assess your faculty development program effectiveness.

Institutions of higher education typically recommend that instructors include a statement regarding support for students with disabilities. You should confirm whether your university has a policy, as well as whether it is required or recommended. However, these statements are often written in such a way that simply puts the responsibility on the student and only offers reactive, accommodations-based solutions. Instead, instructors can model UDL by adding the following statement:

As your instructor, I feel I have a responsibility to do everything within reason to actively support a wide range of learning styles and abilities. As such, I have taken training and applied the principles of Universal Design for Learning to this course. Feel free to discuss your progress in this course with me at any time. In addition, if you require any accommodations, submit your verified accommodations form to me during the first two weeks of the course.

The Chronicle of Higher Education ran an article and discussion on September 9, 2013 about creating syllabus with accomodations.

In order to support faculty on how to frame a course with UDL principles in mind, EnACT~PTD constructed and evaluated a UDL Syllabus Rubric. This rubric and its elements are based on multiple years of research on UDL and course design and delivery. In our development and evaluation efforts, we included extensive input from both instructors and students. As a result, the UDL Syllabus Rubric reflects elements that are considered important to all stakeholders. Faculty are encouraged to use the UDL Syllabus Rubric as a way to reflect upon their current syllabus design and move toward adopting strategies that result in a syllabus that better communicates to and supports all learners.

Following is a list of interesting syllabus examples, particularly in terms of creating a visually engaging syllabus. Instructors are always encouraged to maintain accessible versions (e.g., Word, html).

The Quality Learning and Teaching (QLT) program was developed in 2011 by California State University, Academic Technology Services. Through extensive research and a broad consultative process involving leadership, staff, and faculty at 13 CSU campuses, QOLT has been designed to assist three important aspects of quality online education:

The CSU follows the national, accelerating trend of significant growth in online teaching and learning. The evolution of the Internet and broadband access at home and via mobile devices makes it certain that there will be a continued growth in online courses. In addition, student demand can lead this development, given research that shows students prefer a blended course delivery approach. Online learning provides a diverse group of people the opportunity to participate in higher education.

As CSU campuses offer additional online courses, it is important to define quality online teaching and learning, as well as to determine how to assess it. CSU wants to provide quality education, whether it is online or face-to-face. There are many skeptics who question the quality of online teaching and, therefore, it is necessary to identify how to prepare instructors for teaching online courses effectively. By doing so, we can best prepare instructors and learners for an experience that is equal-to-or-better-than traditional classroom experiences. If successful, the natural evolution of teaching and learning will drive the increased demand for online teaching and learning, as opposed to administrative decisions related to the desire to save money through simple leverage of technology as device.

The QLT evaluation instruments include nine areas of evaluation, comprising 53 discreet objectives. The following list shows the number of items per section in parentheses.

To view the detailed QLT instrument, go to the QLT Instrument page.

There are three commons uses of the QLT rubric:

The Quality Learning & Teaching evaluation instruments were developed after review of related research and literature, as well as careful consideration fo existing models for assessing effective online teaching and learning.

QLT was also shaped by existing research related to effective teaching and learning, such as "Seven Principles of Good Practice in Undergraduate Education" (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). In addition, we have considered an expanded version, titled "Seven (Plus Three) Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education."

QLT Program Director:

A faculty learning community (FLC) is a group of 5 to 7 cross-disciplinary faculty engaging in an active, collaborative, year-long program with a curriculum regarding the enhancement of teaching and learning. Each FLC makes curricular redesign efforts to address a special campus or divisional teaching and learning need, issue, or opportunity (e.g., accessibility). Evidence shows that FLCs increase faculty interest in teaching and learning and provide safety and support for faculty to investigate, attempt, assess, and adopt newer methods.

The process includes frequent seminars and activities that provide learning, development, scholarship of teaching and learning insight, and community building. FLC members work together to reflect on their teaching and providing critical feedback to each other as to infusing UDL within their courses. Training in the structure and format of the EnACT~PTD, FLC is offered through a Universal Design for Learning workshop.

FLC participants select a course to which they: apply the curricular innovation (treatment); assess student learning (effect); and present their results. These faculty members engage in monthly seminars and a retreat, if feasible.

Note, while these are helpful, some still need to address accessibility issues.

Digital stories for faculty development can provide real-life experiences of exemplary teaching strategies and the process of implementing them. These digital case stories can be used freely in faculty development programs and also accessed by individual instructors.

The case stories available here were created by EnACT~PTD (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education, P333A-080027) in partnership with the MERLOT ELIXR program. From 2006-2010, the MERLOT ELIXR Initiative was funded by FIPSE (The Fund for Improvement of Postsecondary Education) with generous support from the California State University, Chancellor's Office, Academic Technology Services, as well as active involvement from over 30 higher education institutions across the U.S. and beyond.

[videos are currently Flash-based and not iOS compatible]

The two-hour UDL workshop serves as a preparatory introduction to the concepts of Universal Design and Universal Design for Learning for faculty, staff and administrators. In addition to introducing these foundational concepts, this session offers participants key examples as to how faculty have incorporated UDL into their teaching practices, as well as “take-away” strategies and additional resources for further exploration.

Previous Faculty

Development directors who have adopted these materials highlight the benefit of

acquiring administrative support to offer this workshop. Given that UDL practices have

shown to have a positive impact on faculty satisfaction and student learning outcomes,

consider providing them with the EnACT~PTD Research Summary which underscores the multiple

benefits of exploring UDL on your campus. In addition, tying this workshop to other

campus-based faculty or administrative priorities (e.g., diversity, graduation rates)

may raise the perceived value and participation.

The

following documents provide you the necessary resources to offer a two-hour UDL workshop

on your campus. Do carefully consider who on your campus is best prepared to offer this

workshop. While not essential, are there faculty, staff, or administrators who may already

have knowledge or expertise in this area?

The specific workshop resources include:

In order to ensure

successful participation for your UDL workshop, consider the optimal timing (calendar) of

the event, as well as day and time. Are there key campus activities or priorities that

align to the workshop goals? Are there particular groups (e.g., new faculty), academic

departments, or committees (e.g., curriculum, diversity, accessibility) that may have a

particular interest in attending or supporting the UDL workshop? Depending upon your

administrative support, this two-hour session can be offered to smaller or larger groups

across campus. To facilitate your call for participation, we have included various

announcements that you can tailor or adapt as needed.

Sustaining interest in

UDL on your campus may be dictated by multiple factors including (a) the ability to

quickly form a Faculty Learning Community aligned to this event, (b) how well the workshop

was received by the participants, and (c) your ability to capture and disseminate any

workshop feedback to the campus community, including key administrators. To support

collecting participant feedback, we have included an editable Workshop/Training

Evaluation form that you can tailor to your specific needs.

Given the central role of teaching and learning to our professional lives, faculty need concrete ways to enhance their effectiveness in the classroom toward supporting greater student achievement. Have you ever asked yourself, “How can I meet the needs of students who struggle to learn, for a variety of reasons, without compromising the rigorous standards of my course?”

This page supports a two-day workshop that offers the foundational knowledge, tools, skills, and resources necessary to effectively implement the principles of UDL. New and emerging technologies will be addressed, in terms of UDL and accessibility. Whether you teach traditional, blended/hybrid, or online courses, UDL can enhance the efficacy of your instruction.

Previous faculty

development directors who have adopted these materials highlight the benefit of acquiring

administrative support to offer this workshop. Given that UDL practices have shown to

have a positive impact on faculty satisfaction and student learning outcomes, consider

providing them with the EnACT~PTD Research Summary which underscores the multiple benefits of

exploring UDL on your campus. In addition, tying this workshop to other campus-based faculty

or administrative priorities (e.g., diversity, graduation rates) may raise the perceived value

and participation.

Use the files below to prepare and deliver Day 1 of a two-day Universal Design for Learning institute. First, access the Overall Agenda and note the flow of the day, which presentation files are available, and accompanying resources you will want to utilize.

Ideally, UDL is implemented with enough depth and breadth to impact course (re)design. By implementing a two-day institute, faculty, faculty developers, and instructional support staff are given the opportunity to discuss UDL, accessibility, student learning outcomes, and respective course experiences.

The institute is best delivered as a collaborative between faculty development and academic support units (e.g., disability support services, academic technology, assistive technology).

Once you have successfully delivered the two-day UDL institute, it is important to collect participant assessment data. In addition, participations may be acknowledged for their efforts through the following Certificate of Participation that you can edit.

The Rubric for Online Instruction (ROI) was developed from 2002-2003 by California State University, Chico, through a broad-based committee comprised of 13 faculty, 4 staff, 2 administrators, and 1 student. This process included dialog and utilization of individual expertise, as well as critical examination of existing scholarly information related to best practices, learning styles, and standards [e.g., Bloom's Taxonomy, Seven Good Teaching Practices in Undergraduate Education (Chickering & Gamson, pdf)].

The resulting ROI addresses six areas, in determining "What a quality course looks like." In addition, CSU Chico has partnered with EnACT~PTD to map the three Principles of Universal Design for Learning with the six areas of the ROI.

The Rubric for Online Instruction (ROI) was developed by California State University, Chico. The ROI addresses six areas, in determining "What a quality course looks like."

There are three commons uses of the CSU, Chico, Rubric for Online Instruction (ROI):

If offering a recognition program, you can follow CSU, Chico's Exemplary Online Instruction (EOI), award nomination process.

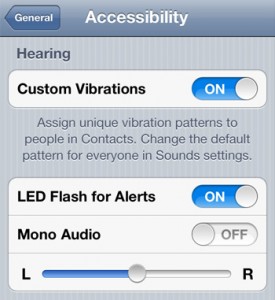

Accessibility is used to describe the degree to which a product, device, service, or environment is available to as many people as possible.

As such, universities all over the world have been improving user access to classrooms and other services and spaces on campus for all students. In addition, universities are also making strides to provide greater access to content and courses.

Think about accessibility from the design stage forward. This not only provides equitable access

to students with disabilities but also provides benefits to many learners without

disabilities.

Examples:

Goal: Students understand course content, and learn.

Old look: Accommodations are modifications or adjustments to a course, program, service, job, or activity that enables a qualified student with a disability to have an equal opportunity. An equal opportunity means an opportunity to attain the same level of performance or to enjoy equal benefits and privileges available to a similarly-situated student without a disability.

New look with UDL: Accommodations are teaching. Every student in higher education should have

the opportunity to learn in the best way possible for them.

Old look: Instructors are required to make a reasonable accommodation according to the

accommodations plan established with university disability support services (DSS).

New look: Instructors are interested in using the UDL framework to make course content and concepts available to all learners.

The following is a list of the most common accommodations services provided to students registered with DSS. Some of these can be provided to everyone, some cannot.

[acknowledgment to CSU Chico, Sonoma State University, and Humboldt State University, September 20, 2011]

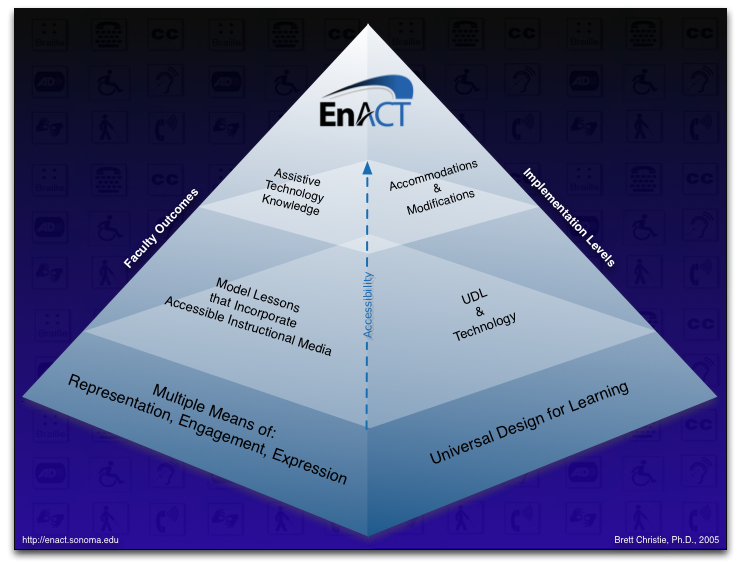

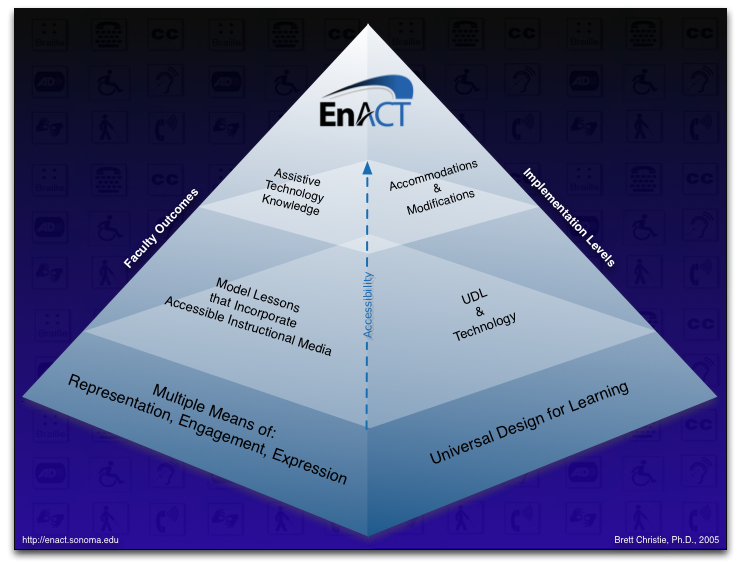

The following graphic represents the three-level approach to implementing Universal Design for

Learning. Faculty to consider accessibility.

Accessibility is used to describe the degree to which a product, device, service, or environment is available to as many people as possible.

As such, universities all over the world have been improving user access to classrooms and other services and spaces on campus for all students. In addition, universities are also making strides to provide greater access to content and courses.

Think about accessibility from the design stage forward. This not only provides equitable access

to students with disabilities but also provides benefits to many learners without

disabilities.

Examples:

Goal: Students understand course content, and learn.

Old look: Accommodations are modifications or adjustments to a course, program, service, job, or activity that enables a qualified student with a disability to have an equal opportunity. An equal opportunity means an opportunity to attain the same level of performance or to enjoy equal benefits and privileges available to a similarly-situated student without a disability.

New look with UDL: Accommodations are teaching. Every student in higher education should have

the opportunity to learn in the best way possible for them.

Old look: Instructors are required to make a reasonable accommodation according to the

accommodations plan established with university disability support services (DSS).

New look: Instructors are interested in using the UDL framework to make course content and concepts available to all learners.

The following is a list of the most common accommodations services provided to students registered with DSS. Some of these can be provided to everyone, some cannot.

[acknowledgment to CSU Chico, Sonoma State University, and Humboldt State University, September 20, 2011]

The following graphic represents the three-level approach to implementing Universal Design for

Learning. Faculty to consider accessibility.

Accessibility for All –

Print Materials

Syllabi and Handouts

PowerPoint

Documents

Images

UDL encourages the use of “accessible” and “usable” course materials for the largest possible audience. Presented here is an expanded explanation of how the UDL framework can boost the effectiveness of course content while keeping course rigor.

A single presentation methodcan prove limiting, for example, when providing a course syllabus.

Syllabus saved in an electronic format can be read aloud by screen reader software or translated into Braille. The same electronic version can be posted on the course LMS.

Screen formats for tablets and cell phones. Focusing on accessible materials, and using the LMS will open your content to different screen formats for accessing everywhere.

Accessible Images

Graphics can be of great benefit to the accessibility of a web page by providing illustrations, icons, animations, or other visual cues that aid comprehension for sighted individuals. Provide those alt-text explanations

Audio

Students with visual impairments, or dyslexia may use screen readers to have any on-screen text spoken aloud. Consider also offering content with audible books or podcasts.

Video

Audio descriptions provide access to multimedia for people who are blind or visually impaired by adding narration that describes the visuals, including action, scene changes, graphics and on-screen text. Captions added to multimedia presentations ensure that the audio components of the presentation are accessible to individuals who are deaf or hard-of-hearing. Captions also provide a powerful search capability, allowing users to search the caption text to locate a specific video, or an exact point in a video.

Developed by the

California State University, Accessible

Technology Initiative.

The National Center on Accessible Instructional Materials serves as a resource for stakeholders, including state- and district-level educators, parents, publishers, conversion houses, accessible media producers, and others interested in learning more about and implementing AIM.

Visit the National Center on Accessible Instructional Materials to learn about the "who, what, why' of AIM, from the basics to classroom and online practice.

President Obama signed the Act into law on October 8, 2010, providing the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) with renewed authority to impose video description requirements on broadcast television stations and certain cable networks. It also requires the FCC to establish closed captioning obligations for some video programming provided over the Internet and to update its emergency information rules.

Closed captioning provides a critical link to news, entertainment and information for individuals who are deaf or hard-of-hearing. For individuals whose native language is not English, English language captions improve comprehension and fluency. Captions can provide a powerful search capability, allowing users to search the caption text to locate a specific video, or an exact point in a video.

Audio descriptions provide access to multimedia for people who are blind or visually impaired by adding narration that describes the visuals, including action, scene changes, graphics and on-screen text.

Captions and audio descriptions may be integrated into multimedia as a user-selectable option (closed) or permanently recorded along with the main audio or video (open). Closed captions and descriptions may be toggled on and off by the user via a preferences setting, a menu option or, in some cases, a button on the player interface. Open captions and descriptions may not be turned off-everyone sees or hears them, whether they want to or not (National Center for Accessible Media).

Web accessibility means that people with disabilities can use the Web, and benefits people without disabilities. More specifically, it means that people with disabilities can perceive, understand, navigate, and interact with the Web, as well as contribute to the Web.

Web accessibility also benefits people without disabilities. For example, a key principle of Web accessibility is designing Web sites and software that are flexible to meet different user needs, preferences, and situations.

Web accessibility encompasses all disabilities that affect access to the Web, including visual, auditory, physical, speech, cognitive, and neurological disabilities. The document "How People with Disabilities Use the Web" describes how different disabilities affect Web use and includes use scenarios.

Making a Web site accessible can be simple or complex, depending on many factors such as the type of content, the size and complexity of the site, and the development tools and environment.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) develops international standards and is an excellent website source for making the web accessible, flexible, and usable for all.

When assessing web accessibility there are a number of "checks" that can take place, whether human or automated. The following is an outline from WebAIM, leading to explanations of human checks, as well as using the Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool (WAVE).

Open Educational Resources (OER) can increase efficiency when materials are published under a license that permits the creation of derivative works (all Creative Commons licenses that do not contain the NoDerivaties (ND) condition allow this). OER can be translated into other languages and transformed into alternate formats–such as for display on mobile devices–more easily than materials published under all rights reserved copyright. MIT OpenCourseWare uses the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license (BY-NC-SA). Nearly 800 MIT OCW courses have been translated into other languages, all without needing to ask permission from the copyright holder.

Bookshare is the world’s largest accessible online library for persons with print disabilities. This access is incredibly important, but the exception is limited, and does not apply for users outside of the United States. Open textbooks are low hanging fruit if they are released under a license that permits the creation of derivative works, because these can be more easily converted into accessible formats, such as audio and Braille refresh. No extra permissions costs have to be incurred or royalties paid for these adaptations to take place.

From 2010-2011, the College Open Textbooks Collaborative contracted with Virtual Ability, Inc to develop a process for reviewing college-level open textbooks regarding accessibility. The criteria used for the reviews were drawn from US accessibility legal requirement expressed in Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and international accessibility guidelines of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

Accessibility criteria for open texts can be grouped under the acronym POUR (Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, and Robust). The linked report is a good summary of how 60 online open texts, web and pdf, were reviewed for accessibility ad what main challenges remain.

Blind students should not be excluded from physics (or any) courses because of inaccessible textbooks. A good example of a text that is OER and designed to support students with disabilities in acquiring the necessary content, knowledge, and skills is "Accessible Physics Concepts for Blind Students."

The modules in this text present physics concepts in a format that blind students can read using accessibility tools. These modules are intended to supplement and not to replace the physics textbook.

Access to OER is growing, but, not for all. Not only do the online educational materials need to be freely available and with permission to use, OER need to be designed so individuals with disabilities can use them for their teaching and learning. The California State University (CSU), MERLOT (Multimedia Educational Resources for Learning and Online Teaching), Open Courseware Consortium (OCWC), the National Federation of the Blind (NFB), and Flexible Learning for Open Education (FLOE) have partnered together on a joint mission to enable the community of accessible technology experts, advocates, and users to build an online community and collection of OER that may improve universal learning by facilitating the contribution and sharing of accessible technology information, expertise, and accessible online teaching and learning materials.

To advance their mission of accessibility and OER, MERLOT created an accessible, online community website by leveraging their open educational services, http://oeraccess.merlot.org.

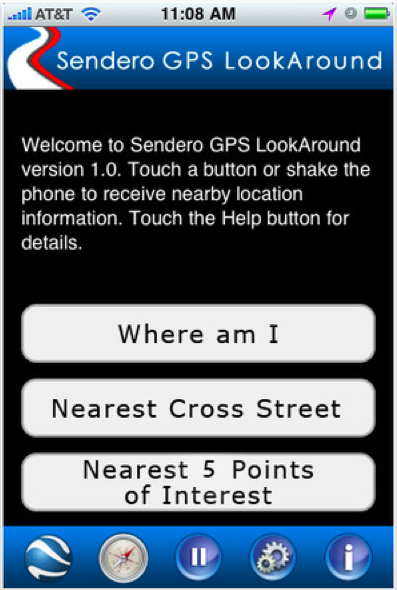

Rapid development in both numbers and functionality of mobile apps continues. Many of these are accessible to all users, given the increased attention being paid to accessibility and universal design of both hardware and software.

UDL has research in two overall categories; the research that created Universal Design for Learning, and the research that explores using the lens of UDL. While the research that led to the founding of UDL as a framework involved a meta-analysis of literature on brain research, neuroscience, and education among several other fields, is conceptually completed, the research into UDL as a practice is just beginning.

The following categories here highlight some of the research, and point readers toward other studies.

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of postsecondary education and disability, 19(2), 135-151.

Abstract: Authored by the teaching staff of T-560: Meeting the Challenge of Individual Differences at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, this article reflects on potential applications of universal design for learning (UDL) in university courses, illustrating major points with examples from T-560. The article explains the roots of UDL in cognitive neuroscience, and the three principles of UDL: multiple means of representing information, multiple means of expressing knowledge, and multiple means of engagement in learning. The authors also examine the ways UDL has influenced their course goals and objectives, media and materials, teaching methods, and assessment techniques, including discussion groups, lectures, textbooks, and the course website. The authors emphasize the ongoing developmental nature of the course and UDL principles as tools or guidelines for postsecondary faculty, rather than a set of definitive rules. UDL is proposed as a way to address diversity and disabilities as constructs of individuals and their environment in higher education classrooms.

Rao, K., Ok, M. W., & Bryant, B. R. (2014). A review of research on universal design educational models. Remedial and Special Education, 35(3), 153-166.

Abstract: Universal design for learning (UDL) has gained considerable attention in the field of special education, acclaimed for its promise to promote inclusion by supporting access to the general curriculum. In addition to UDL, there are two other universal design (UD) educational models referenced in the literature, universal design of instruction (UDI) and universal instructional design (UID). This descriptive review of 13 research studies conducted in pre-K–12 and post-secondary settings examined how researchers are applying and evaluating UD in educational settings. Results of the review illustrated that studies use a range of research designs to examine student outcomes and participant perceptions of UD-based curriculum and instruction. Researchers report on their application of UD principles in varied ways, with no standard formats for describing how UD is used. Based on results of the review, we provide recommendations to help establish a meaningful research base on the validity of UD in education.

Catalano, A. (2014). Improving distance education for students with special needs: A qualitative study of students’ experiences with an online library research course. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 8(1-2): 17-31. doi: 10.1080/1533290X.2014.902416

Abstract: This article describes a study in which seven students with diverse disabilities participated in a one-credit online library research course which had been adapted to be accessible using the best practices literature on distance education for students with special needs. Students provided feedback on the design of the course and participated in in-depth interviews. Results of this study suggest any given class may have students with different types of disabilities, with different paths toward learning. Using the principles of universal design for learning can improve distance education not only for students with special needs, but for all types of learners.

Al-Azawei, A., Parslow, P., & Lundqvist, K. (2017). The effect of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) application on e-learning acceptance: A structural equation model. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(6).

Abstract: Standardizing learning content and teaching approaches is not considered to be the best practice in contemporary education. This approach does not differentiate learners based on their individual abilities and preferences. The present research integrates a pedagogical theory Universal Design for Learning (UDL)with an information system (IS) theory Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). It aims to examine the effectiveness of a technology-enhanced traditional web design course on blended e- learning acceptance and learner satisfaction in which UDL principles (multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement) were implemented. This casts some light on the role of addressing curricula limitations on learner perceptions and e-learning adoption. A mixed research design combining survey and action methods was followed. Overall, 92 undergraduate students took part in the study. The research instrument was validated first. Subsequently, partial least squares-structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was applied to identify the path associated among constructs used in the proposed framework. The extended model accounted for 45.4% and 41.6% of the variance of perceived satisfaction and behavioural intention respectively. The findings suggest that using educational technologies to address curricula limitations is a bridge to enhancing learner willingness to accept e-learning.

Goegan, L. D., Radil, A. I., & Daniels, L. M. (2018). Accessibility in Questionnaire Research: Integrating Universal Design to Increase the Participation of Individuals with Learning Disabilities. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 16(2), 177-190.

Abstract: This paper explores how to apply the principles of accommodations and universal design (UD) in research methods involved in quantitative research (e.g. questionnaires). In particular, we focus on how to make research more accessible for individuals with Learning Disabilities (LD), while also providing suggestions for potential participants of research more generally. This paper first reviews accommodations provided to students within an educational setting, focusing on the components of setting, timing, presentation and response format. Following this discussion, we discuss UD and how it can be adapted to the research process (e.g. the creation of surveys, and data collection). Next, we draw on components of accommodations and universal design to offer suggestions for those conducting research with individuals with LD. In closing, we provide a table with key UD and accommodation questions that researchers can use to guide questionnaire design thereby advancing the field when it comes to accessible research design.

The research used to develop UDL can be found on the udlguidelines.cast.org website using the following directions:

The research is presented in two categories: Experimental and Qualitative Evidence, and Scholarly Reviews and Expert Opinions.

The book Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice is an excellent source written by some of the original scientists and scholars on the theory surround UDL. This book is open source and can be accessed for free. You will need to sign up with CAST as directed to have access.

UDL has research in two overall categories; the research that created Universal Design for Learning, and the research that explores using the lens of UDL. While the research that led to the founding of UDL as a framework involved a meta-analysis of literature on brain research, neuroscience, and education among several other fields, is conceptually completed, the research into UDL as a practice is just beginning.

The following categories here highlight some of the research, and point readers toward other studies.

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of postsecondary education and disability, 19(2), 135-151.

Abstract: Authored by the teaching staff of T-560: Meeting the Challenge of Individual Differences at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, this article reflects on potential applications of universal design for learning (UDL) in university courses, illustrating major points with examples from T-560. The article explains the roots of UDL in cognitive neuroscience, and the three principles of UDL: multiple means of representing information, multiple means of expressing knowledge, and multiple means of engagement in learning. The authors also examine the ways UDL has influenced their course goals and objectives, media and materials, teaching methods, and assessment techniques, including discussion groups, lectures, textbooks, and the course website. The authors emphasize the ongoing developmental nature of the course and UDL principles as tools or guidelines for postsecondary faculty, rather than a set of definitive rules. UDL is proposed as a way to address diversity and disabilities as constructs of individuals and their environment in higher education classrooms.

Rao, K., Ok, M. W., & Bryant, B. R. (2014). A review of research on universal design educational models. Remedial and Special Education, 35(3), 153-166.

Abstract: Universal design for learning (UDL) has gained considerable attention in the field of special education, acclaimed for its promise to promote inclusion by supporting access to the general curriculum. In addition to UDL, there are two other universal design (UD) educational models referenced in the literature, universal design of instruction (UDI) and universal instructional design (UID). This descriptive review of 13 research studies conducted in pre-K–12 and post-secondary settings examined how researchers are applying and evaluating UD in educational settings. Results of the review illustrated that studies use a range of research designs to examine student outcomes and participant perceptions of UD-based curriculum and instruction. Researchers report on their application of UD principles in varied ways, with no standard formats for describing how UD is used. Based on results of the review, we provide recommendations to help establish a meaningful research base on the validity of UD in education.

Catalano, A. (2014). Improving distance education for students with special needs: A qualitative study of students’ experiences with an online library research course. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 8(1-2): 17-31. doi: 10.1080/1533290X.2014.902416

Abstract: This article describes a study in which seven students with diverse disabilities participated in a one-credit online library research course which had been adapted to be accessible using the best practices literature on distance education for students with special needs. Students provided feedback on the design of the course and participated in in-depth interviews. Results of this study suggest any given class may have students with different types of disabilities, with different paths toward learning. Using the principles of universal design for learning can improve distance education not only for students with special needs, but for all types of learners.

Al-Azawei, A., Parslow, P., & Lundqvist, K. (2017). The effect of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) application on e-learning acceptance: A structural equation model. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(6).

Abstract: Standardizing learning content and teaching approaches is not considered to be the best practice in contemporary education. This approach does not differentiate learners based on their individual abilities and preferences. The present research integrates a pedagogical theory Universal Design for Learning (UDL)with an information system (IS) theory Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). It aims to examine the effectiveness of a technology-enhanced traditional web design course on blended e- learning acceptance and learner satisfaction in which UDL principles (multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement) were implemented. This casts some light on the role of addressing curricula limitations on learner perceptions and e-learning adoption. A mixed research design combining survey and action methods was followed. Overall, 92 undergraduate students took part in the study. The research instrument was validated first. Subsequently, partial least squares-structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was applied to identify the path associated among constructs used in the proposed framework. The extended model accounted for 45.4% and 41.6% of the variance of perceived satisfaction and behavioural intention respectively. The findings suggest that using educational technologies to address curricula limitations is a bridge to enhancing learner willingness to accept e-learning.

Goegan, L. D., Radil, A. I., & Daniels, L. M. (2018). Accessibility in Questionnaire Research: Integrating Universal Design to Increase the Participation of Individuals with Learning Disabilities. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 16(2), 177-190.

Abstract: This paper explores how to apply the principles of accommodations and universal design (UD) in research methods involved in quantitative research (e.g. questionnaires). In particular, we focus on how to make research more accessible for individuals with Learning Disabilities (LD), while also providing suggestions for potential participants of research more generally. This paper first reviews accommodations provided to students within an educational setting, focusing on the components of setting, timing, presentation and response format. Following this discussion, we discuss UD and how it can be adapted to the research process (e.g. the creation of surveys, and data collection). Next, we draw on components of accommodations and universal design to offer suggestions for those conducting research with individuals with LD. In closing, we provide a table with key UD and accommodation questions that researchers can use to guide questionnaire design thereby advancing the field when it comes to accessible research design.

The research used to develop UDL can be found on the udlguidelines.cast.org website using the following directions:

The research is presented in two categories: Experimental and Qualitative Evidence, and Scholarly Reviews and Expert Opinions.

The book Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice is an excellent source written by some of the original scientists and scholars on the theory surround UDL. This book is open source and can be accessed for free. You will need to sign up with CAST as directed to have access.

CSU faculty perception of

EnACT~PTD project trainings and

activities revealed high levels of satisfaction that met or exceeded their expectations.

Specifically, faculty offered praise for the UDL Workshop (88% satisfaction rate); praise

for the FLC forum (89% satisfaction); and noted the overall importance of their course

changes in light of the teaching and learning process (97% noted as important). Of

particular interest, 72% of the faculty stated they would have been “unlikely” or “not made”

course changes had they not participated in

EnACT~PTD.

In a follow-up qualitative study, faculty were interviewed to gain insight into their perceptions regarding EnACT~PTD processes on their respective campuses. Key findings from these interviews revealed that the FLC process was valued as a tool to “improve the quality and effectiveness of teaching and improving accessibility for all students.” As well, faculty praised the UDL process as a way to “reach everyone regardless of learning style” and that the overall format was valued by the participants given that they “clearly see the benefits to student learning.” Commonly, the highest value was placed on how FLC members offer support and insight to each other on “how to teach a class so that information and conceptualization of course concepts is universally accessible to all students via diverse teaching methods.”

The Research Briefs included in this section offer a more in-depth look at the impact of the EnACT~PTD faculty development model and related resources.

The following 1-page research briefs serve as a synthesis of our latest research on the impact of UDL upon student outcomes.

During the Fall 2010 term, 1,811 students were enrolled in the 37 EnACT~PTD project-targeted courses. Of those enrolled, 6% were students with disabilities (SwD) and 94% were students without disabilities (SwoD). Students were primarily undergraduates (72%) and primarily female (66%). At the end of the Fall term, faculty identified their unique UDL course changes and asked their students to evaluate the relative importance of these changes. Data revealed that students with and without disabilities demonstrated statistically similar perceptions (p>.05) regarding the importance of these unique UDL courses changes. Specifically, all students (regardless of disability status) noted that their instructor's course changes were “important” (mean 2.49) in helping them succeed in class. This is corroborated by data collected on their overall course achievement. On average, SwD maintained a Grade Point Average (GPA) of 3.04 while SwoD maintained a 2.97 GPA.

In addition, all students were asked to evaluate the relative importance of our project-based UDL Common Elements. Parallel findings were noted in that students with and without disabilities held statistically similar perceptions (p>.05) that the UDL Common Elements were “important” in helping faculty create an effective learning environment. Students also offered substantive narrative feedback on how UDL course changes impacted their success including: “having a more complete syllabus,” “frequent quizzes as opposed to longer tests,” and “the opportunity to let us revise assignments was very helpful.”

The Research Briefs included in this section offer a more in-depth look at the impact that UDL course changes had on student success/achievement.

The following 1-page research briefs serve as a synthesis of our latest research on the impact of UDL upon student outcomes.

Emiliano Ayala, Ph.D.,

Co-Director

Brett Christie, Ph.D.,

Co-Director

Janet Hardcastle,

Administrative Specialist

EnACT~PTD received $1,022,595 from the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education, (Award # P333A080027; Oct 2008 - Sept 2012). The EnACT~PTD grant is "A Demonstration Project to Ensure Students with Disabilities Receive a Quality Higher Education."

Ensuring Access through Collaboration and Technology (EnACT) received $1,010,671 from the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Postsecondary Education, (Award # P333A050066; Oct 2005 - Jul 2010). The EnACT grant was "A Demonstration Project to Ensure Students with Disabilities Receive a Quality Higher Education."

In addition, the California State University, Office of the Chancellor provided $91,354 in support of EnACT goals.

Sonoma State University

San Francisco State University

San José State University

CSU, Monterey Bay

CSU, Sacramento

Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo

Project Evaluators

California State University, Center for Distributed Learning

California State University, Accessible Technology Initiative

Multimedia Educational Resource for Learning and Online Teaching (MERLOT)

EnACT~PTD Project Documents